Custom Observability Tooling Sagas: The Spring Boot Actuator CLI

Preface#

A substantial part of modern service infrastructure involves delivering an application (server / backend / service / micro-service / API). The intention of this application could be anything—serving a rendered page, a REST API, a WebSocket stream, or a message queue worker.

While building the application is one challenge, the real “boss-fight” begins once the application is deployed to production and the team needs to support it. Supporting the application ranges from simple tasks, like figuring out which version is deployed, to complex challenges, like mutating a configuration in flight.

Due to the ubiquity of these tasks, teams often dive into building custom tooling to gain observability and insights into said applications. Building these tools has almost become a rite of passage in modern application development. After having built a few, I wanted to capture the nuances, design decisions, and lessons learned.

Spring Boot…?#

In a nutshell, Spring Boot is a framework for building applications in Java. Think Express in Node, Rails in Ruby, or Django in Python. The Spring project pieces together many popular Java projects into a palatable, yet extensible experience.

While Spring provides the base to build your applications, the rest of the Spring ecosystem provides answers for almost every possible type of integration—from Kafka to Kubernetes.

Note: While Spring is excellent for quickly standing up applications, I have personally found it to be a bit “magical” in its details, often requiring workarounds if you don’t agree with the “Spring way.” However, its ease of use and strong ecosystem make it a formidable candidate for application development.

Spring Boot Actuator…?#

Actuator is a vital member of the Spring ecosystem. Once installed into a Spring application, this module exposes a variety of REST endpoints that can be programmatically queried to facilitate application management.

After setting it up, Actuator is available through the /actuator endpoint. Here is a sample response:

// GET /actuator

{

"_links": {

"beans": { "href": "http://localhost:8080/actuator/beans", "templated": false },

"env": { "href": "http://localhost:8080/actuator/env", "templated": false },

"health": { "href": "http://localhost:8080/actuator/health", "templated": false },

"logfile": { "href": "http://localhost:8080/actuator/logfile", "templated": false },

"prometheus": { "href": "http://localhost:8080/actuator/prometheus", "templated": false }

}

}

The /actuator endpoint acts as a discovery endpoint, listing available capabilities.

- Read Operations: The

/healthactuator is a dead-simple read operation. Other components (like Spring Kafka or Data JPA) can implement the Health Indicator API to submit custom status checks here. - Write Operations: The

/envactuator allows you to mutate the application’s environment or configurations at runtime.

For example, updating a db_password config in runtime without a restart:

$ curl \

-X POST \

-d '{"name":"db_password", "value":"hunter2"}' \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

http://localhost:8080/actuator/env

Other powerful endpoints include:

/threaddump: Essential for deep debugging./loggers: Allows you to toggle logging levels (e.g.,INFOtoDEBUG) on a class-path level in runtime./logfile: Streams the log file directly to the response.

The Problem: Interface vs. Client#

All these endpoints make Actuator a great debug tool, right?

Not exactly. Actuator is an interface. Like any interface, it needs a good client to drive it.

My previous role involved supporting ~12 Spring applications across three teams. We managed multiple instances across Dev, QA, and Prod. In the heat of an incident, even introspecting the health of an application became a massive chore.

I often saw coworkers wrestling with bash scripts, complex curl commands, and jq queries just to parse JSON responses. As the number of environments grew, this approach became unmanageable. While tools like Postman or Insomnia exist, none hit the “apex” of requirements:

- Ease of use/setup.

- Intelligent parsing (understanding what the response means).

- Secure config storage for credentials and variables.

Enter: Spring Boot Actuator CLI#

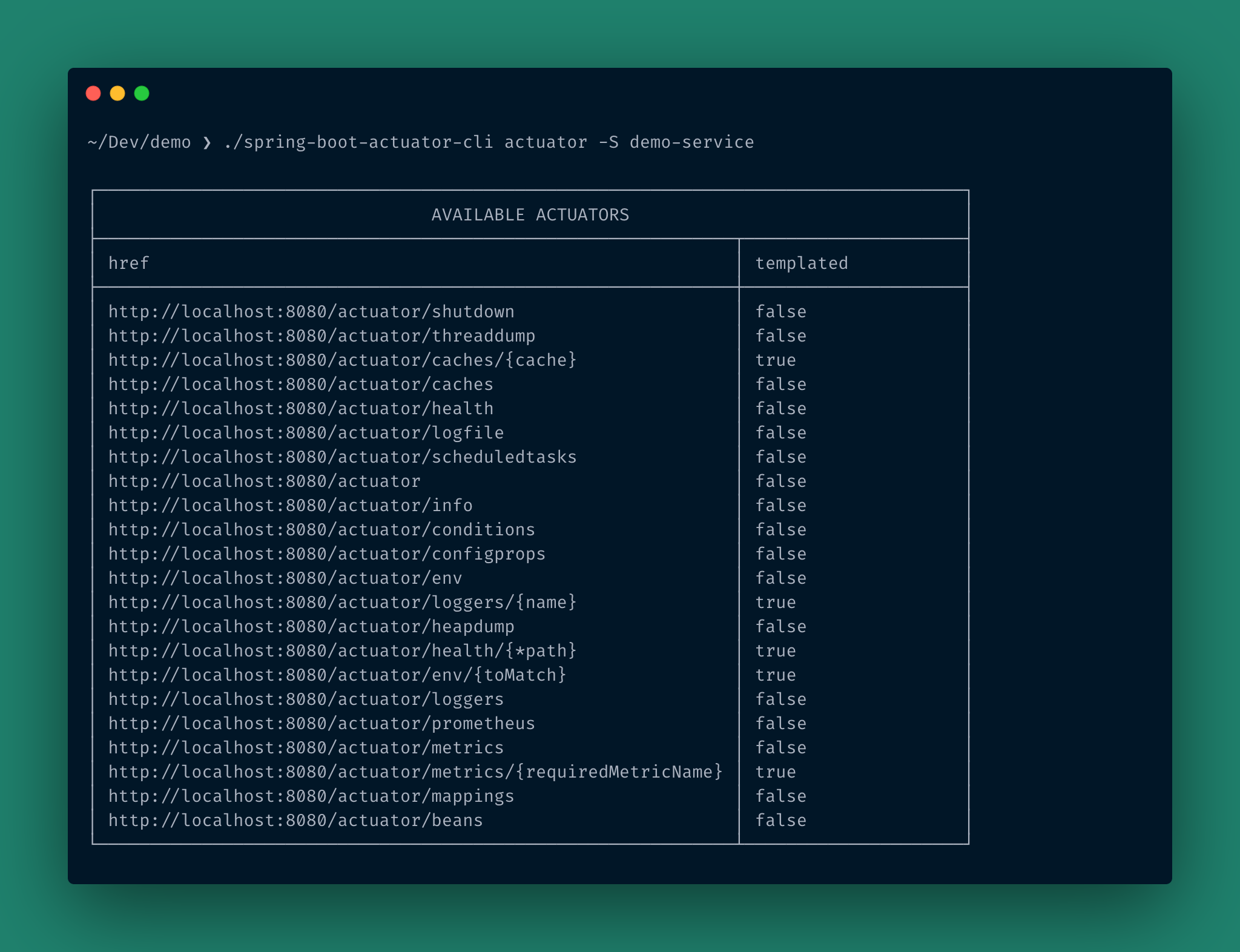

In early 2021, I built spring-boot-actuator-cli (sba-cli), a command-line application designed to interact with and visualize Actuator data.

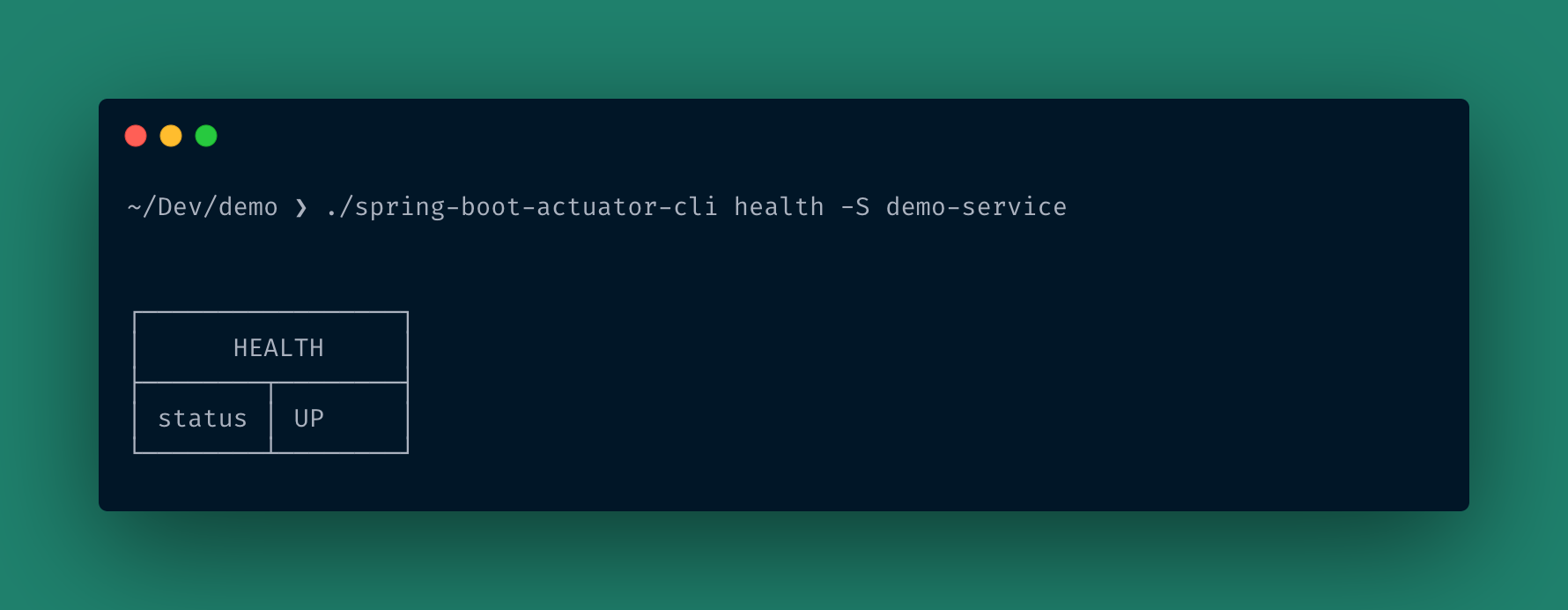

Here is the most basic usage—hitting the /health actuator of a local application:

$ ./sba-cli health -U http://localhost:8080

┌─────────────────┐

│ HEALTH │

├────────┬────────┤

│ status │ UP │

└────────┴────────┘

The CLI figures out the correct REST call, parses the JSON, and outputs a human-readable table.

Inventory Management#

To handle multiple microservices, sba-cli uses an Inventory system defined in a config.yaml file.

inventory:

- name: demo-service

baseURL: http://localhost:8080

skipVerifySSL: true

tags: [demo, local]

- name: demo-service-prod

baseURL: https://demo-service-prod

tags: [demo, prod]

- name: auth-service-prod

baseURL: https://auth-service-prod

authorizationHeader: Basic YXJraXRzOmh1bnRlcjI=

tags: [auth, prod]

You can then target specific services by name rather than remembering URLs:

$ ./sba-cli info -S demo-service

>>> demo-service

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│ SERVICE INFO │

├──────────────┬──────────────┤

│ title │ demo-service │

└──────────────┴──────────────┘

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ GIT INFO │

├─────────────────┬──────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ branch │ main │

│ commit.abbrev │ c6c4cdb │

└─────────────────┴──────────────────────────────────────────┘

Tagging and Bulk Actions#

A powerful feature for complex inventories is Tagging. You can query all services that match a specific tag, allowing for bulk health checks across an entire environment.

# Query all services tagged "prod"

$ ./sba-cli health -T prod

>>> auth-service-prod

┌─────────────────┐

│ HEALTH │

├────────┬────────┤

│ status │ DOWN │

└────────┴────────┘

>>> demo-service-prod

┌─────────────────┐

│ HEALTH │

├────────┬────────┤

│ status │ UP │

└────────┴────────┘

Collaboration via Git#

The inventory file approach allows teams to commit the config to a “secrets” repository. This enables collaborative updates—if a URL changes, one person updates the repo, and the whole team gets the change via git pull.

Under the Hood: Technical Nuances#

1. New curl, who dis?#

Handling the HTTP lifecycle in a corporate environment is rarely straightforward. You have to deal with magic auth headers, proxy ports, and questionable self-signed SSL certificates.

In sba-cli, I abstracted this into a MakeHTTPCall function. It centralizes the complexity of setting up the client, awaiting responses, and error handling.

The UI/UX mirrors curl flags to ensure a familiar experience for developers:

$ ./sba-cli health -h

Flags:

-H, --auth-header string Authorization Header

-K, --skip-verify-ssl Skip verification of SSL

-S, --specific string Name of a specific Inventory

-U, --url string URL of the target Spring Boot app

2. The Challenge of Dynamic Structures in Go#

Parsing Actuator responses is tricky because they are often dynamic. For example, /env returns a dump of configurations with keys that are unknown at compile time.

Unlike JavaScript, Go (GoLang) is statically typed and prefers knowing the type definition when marshalling JSON. To solve this, I used the dynamic-struct library.

While functional, it creates a syntax overload that impacts readability. Here is how I parse the /actuator response to extract hrefs:

// build the dynamicstruct based on the response

reader := MakeDynamicStructReader(ActuatorInfoProperties{}, actuatorResponse)

// Extract "Links" map and iterate

for _, link := range reader.GetField("Links").Interface().(map[string]interface{}) {

var href string

// Iterate through link properties

for v_k, v_v := range link.(map[string]interface{}) {

if v_k == "href" {

href = fmt.Sprintf("%v", v_v)

}

}

t.AppendRow(table.Row{href, templated})

}

Even with comments, the heavy use of interface{} casting makes the code difficult to scan. This is an avenue I plan to refactor and explore further.

Closing Thoughts#

Building sba-cli touched on various aspects of engineering—from HTTP client architecture to CLI user experience design.

Building tooling for humans can be challenging, exhausting, and occasionally obtuse, but it is nonetheless rewarding. There is a distinct satisfaction in seeing a teammate’s workflow improve, thereby increasing their effectiveness and reducing the stress of on-call support.

Special thanks to @cyber_junkie 🙏